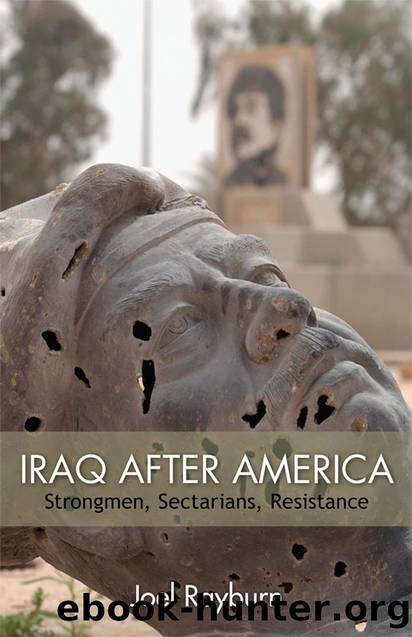

Iraq After America: Strongmen, Sectarians, Resistance by Joel Rayburn

Author:Joel Rayburn [Rayburn, Joel]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: International Relations, Political Science, History, Politics, General

ISBN: 9780817916947

Google: u7I_BAAAQBAJ

Goodreads: 22309493

Publisher: Hoover Institution Press

Published: 2014-08-01T00:00:00+00:00

THE STRUGGLE FOR ASSYRIA

Far northwest of the Kirkuk and Diyala battlefields, Sunni chauvinism and Kurdish maximalism collided in a violent, high-stakes contest for the city of Mosul and the plains of Ninewa. The war in Ninewa played out on many levelsâethnic, sectarian, tribal, and othersâowing mainly to Mosulâs particular geography and demography. Modern Mosul, a city of almost two million people, lay adjacent to the ruins of the biblical city of Nineveh, the imperial capital of Assyria for which the surrounding province is named. For thousands of years, the city had sat at a crossroads of great empires and cultures, giving it an unusually cosmopolitan nature, with a Sunni Arab majority living mainly peacefully alongside large minorities of Kurds, Assyrian and Sabean Christians, Turcomans, and a dizzying array of smaller sects and ethnicities. Since Roman times, the east-west Silk Road had run through Mosul, connecting the region to both the Mediterranean and China, making the cityâs livelihood more dependent on the flow of goods and people west to Aleppo than south to Baghdad. For much of its modern history, Mosul was not so much an Iraqi outpost on the southern edge of Ottoman Anatoliaâand eastern Syriaâas it was an Ottoman outpost on the edge of Arab Iraq, a province equal in stature to Baghdad and Basra, ruled directly from Constantinople.

Mosulâs inclusion in the modern Baghdad-centered Iraqi state had been somewhat accidental. When the European powers met in Paris in 1919 to divide the Arab lands of the Ottoman Empire, Mosul and its region were originally meant to be part of French Syria, and were only transferred to British control as the result of a personal agreement between Lloyd George and Clemenceau. Even then, it was not clear that Mosul would be permanently incorporated into the new post-Ottoman Iraq. British armies had entered Mosul days after the Anglo-Ottoman armistice of 1918, not before, and Kemalist Turkey continued to claim it as an Ottoman city. Ataturk and his forces periodically threatened to seize the city until the League of Nations formally awarded it to Baghdad in 1925, dashing the hopes of a substantial portion of Mosulawis who did not relish the idea of being subordinated to a new British-dominated government in Baghdad.

The annexation of Mosul into the new Iraq was not the last time the powerful men of Mosul would find themselves unhappy with a newly established political arrangement. A few months after the leftist military dictator Abd al-Karim Qasim seized power in Baghdad in 1958, the pro-Nasser military garrison of Mosul mutinied against the new regime and its communist allies, aiming to take power and join Iraq to the new United Arab Republic of Egypt and Syria. Though the revolt collapsed in short order, it indicated the underlying support for Arab nationalist parties in Mosul, and it also established a pattern: when power changed hands in Baghdad, Mosulawis would not necessarily accept the new order.

The practical consequence of this history is that when the Sunni Arabs of Ninewa found themselves pushed

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7125)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6948)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5415)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5370)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5196)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5178)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4313)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4190)

Never by Ken Follett(3955)

Goodbye Paradise(3810)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3772)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3396)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3085)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3073)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3029)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2925)

Will by Will Smith(2919)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2845)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2736)